The Truth Crisis

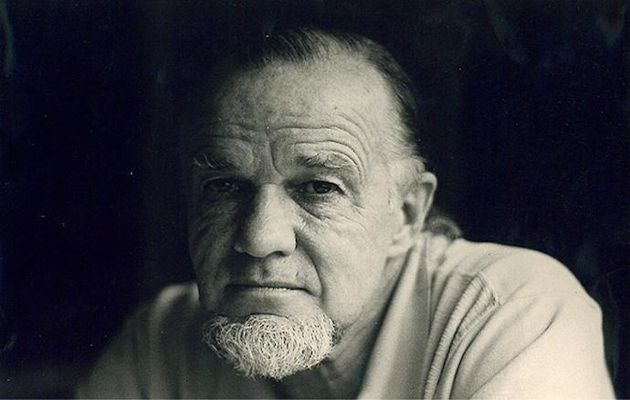

Francis Schaeffer sets the tone for his apologetical procedure by explaining the crisis of truth in America: “We are fundamentally affected by a new way of looking at truth. This change in the concept of the way we come to knowledge and truth is the most crucial problem facing America today” (The God Who Is There, 6). He believes a paradigm shift occurred around 1935 when the American attitude toward truth changed. Prior to this time, American’s were devoted to thinking about presuppositions, namely, the existence of absolutes, particularly in the areas of morals (ethics) and knowledge (epistemology). But the average American took it for granted that if a certain idea was true, it’s opposite was false. In other words, “absolutes imply antithesis.” The working antithesis is that God exists objectively (in antithesis) to his not existing.

Schaeffer believes that presuppositional apologetics would have stopped the decay. Incidentally, he maintains that the use of classical apologetics was effective prior to the shift because non-Christians were functioning on the surface with the same presuppositions, even though they did not have an adequate base for them.

The Role of Thomas Aquinas

Dr. Schaeffer maintains that Aquinas opened the way for the discussion of what is usually called the “nature and grace” controversy (Escape From Reason, 209). He contends that Aquinas set up a dichotomy of grace versus nature.

Aquinas taught that the will of man was fallen, but the intellect was not. The net result, according to Schaeffer, is that man’s intellect is seen as autonomous. Schaeffer maintains that the teaching of Aquinas led to the development of the so-called Natural Theology where theology could be pursued independent of the Scriptures. The vital principle to understand according to Schaeffer is that “as nature was made autonomous, nature began to ‘eat up’ grace” (Escape From Reason, 212).

Anthropology

Schaeffer militates against this so-called “grace/nature” dichotomy and insists that Christ is equally Lord in both areas. He suggests that God made the whole man and is consequently interested in the whole man. When the historic space-time Fall took place, it affected the whole man, not merely the will as Aquinas taught. Thus, Schaeffer taught that the whole man is saved and the whole man will eventually be glorified and perfectly redeemed.

Since God made man in His own image, man is not caught in the wheels of determinism: “The Christian position is that since man is made in the image of God and even though he is a sinner, he can do those things that are tremendous – he can influence history for this life and the life to come, for himself and others” (Death In The City, 258).

Schaeffer argues that Evangelicals have such a strong tendency to combat humanism that they end up making man a “zero.” He adds, “Man is indeed lost but that does not mean he is nothing . . . From the biblical viewpoint, man is lost, but great” (Death In The City, 258-259). Therefore, Schaeffer’s anthropological position is that man is sinful, yet he is significant because he is made in the image of God. And regenerate man is, as the Reformers emphasized, simul iustus et peccator – simultaneously righteous and sinful.

Reblogged this on Truth2Freedom's Blog.